These are my notes for the sermon I delivered on Erev Rosh Hashanah 5786 / September 22, 2025. Of course, I always go off script a bit, so I’m also including the video. I’d love to hear what you think!

~ Reb Josh.

Shanah tovah!

It’s good to see you all here! It’s been a year since we’ve all been here together. My second year here! I’m starting to feel at home.

Which go me wondering: what does it mean to feel at home? How does one feel at home?

My wife likes to tell guests:

Your first time here, you sit down and we serve you.

The second time, come in and help yourself.

The third time, you’re part of the family, and we put you to work!

Last year I was just introducing myself. This year, I feel I’m part of the family. I know where to find things in the Vestry and in the JCH kitchen. When I look through the faces in the Facebook group, I know most of the names, even if we don’t see each other very often. (I don’t know everybody yet… so that’s my project for this coming year!)

I know who to call when I need a hand with something, and I trust you’ll reach out to me if you need something from me—or if I’ve made a mistake you need me to correct! I know I’m far from perfect, and I’m always grateful when you let me know how I can do better and give me a chance to do teshuvah and set things right.

And I know I can express my opinions about things, and I trust you’ll tell me if you disagree! (After all: two Jews, three opinions!)

I’m also privy to some of the family-like dynamics where certain people don’t talk to certain other people about certain things, because they think they already know they’ll disagree.

Sometimes we stay quiet about things that are important to us, because we don’t want to “get into it.” We don’t want to be judged, and we don’t want to judge each other. But here’s the thing: we are still in community together.

We may disagree with each other about Israel and Palestine, or what flag to hang (or not to hang) outside our building, or the policies of the US government at any given time. There may be important, principled, and personal reasons for disagreement, and there are usually painful histories behind them. But last Shabbat we prayed together, and the week before that we attended a shiva together, and last month we worked on a fundraiser together.

And that counts for something. Actually, that counts for a lot. Because for a congregation to build a home together—that really takes intentionality.

The Hebrew word for that is Kavanah.

Towards the beginning of the Talmud, in the second chapter of the first tractate, Berachot, which deals with prayers, the rabbis contemplate a law that they have inherited from their teachers. The Mishna says (and I’m paraphrasing just a tiny bit): “If a person was reading chapter 6 of Deuteronomy, where the Shema is written, and it happens to be the time for reading the Shema in prayer, that person has fulfilled the obligation for prayer if they set their heart on the intention.”

The rabbis of the Talmud say: “Oh! So apparently to get credit for doing a mitzvah, you need kavanah—you need some sort of intention!” But then they ask: how can you read without the intention to read? I mean, you’re reading! Well, they propose, maybe it’s a case of someone who’s just proofreading… To count as having read the Shema, you have to actually pay attention to the words and what they mean. You need to have some sort of kavanah. (This passage, by the way, is why we close our eyes and concentrate when we recite the Shema.)

It’s the same way with community. Being a member of a community is more than just paying dues, or getting the newsletter and the emails, or just happening to be in the building at the same time. To be a community, you need to have kavanah. Some sort of intention to be part of the community.

Remember the symbolism behind shaking the lulav and etrog on Sukkot? The midrash says: some of the plants have flavor, some have taste, some have neither, some have both—and that’s the people of Israel. Different people have different talents and different capacities. And the question is: can the lulav and etrog shake together?

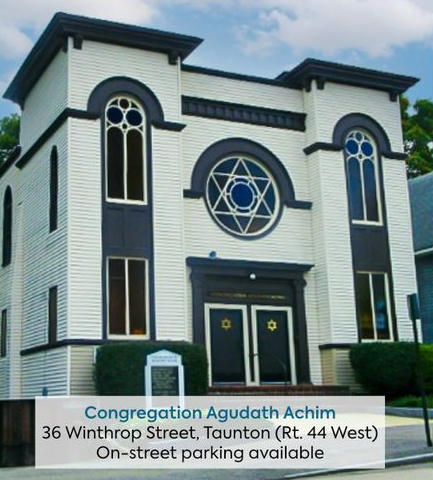

Can we, Congregation Agudath Achim—this Family of Friends (or the people of Israel as a whole, for that matter)—function and flourish together as a single community, not despite our differences, but precisely because of them?

Let me explain what I mean by flourishing precisely because of our differences.

Anyone know what the word “Israel” means? It means “God-Wrestlers.”

Yaakov Avinu—our father Jacob—was given that name by a mysterious, supernatural “man” he wrestled with all night. And when they reached a draw before dawn, and the man wanted to leave, Jacob told him: “I will not let you go until you bless me.” And that’s when this supernatural being, this angel, told Jacob: “Your name isn’t Jacob anymore. It’s Yisra-el. God-wrestler. Ki sarita im Elohim v’im anashim vatuchal: because you have struggled with God and with people, and you’ve survived.”

Isn’t it interesting that we define ourselves—in our very name—by this experience, as strugglers? We struggle with God, with our tradition, and with each other.

“Because you have struggled with God and with people, and you’ve survived.”

But not just survived. Blessed. “I will not let you go until you bless me,” Jacob said—and the angel did. Jacob comes away changed. The struggle literally defines him. He is now “God-wrestler,” and blessed by that name.

That word vatuchal is usually translated “and have triumphed.” But the root of the word yachol just means “able.” What was it that Jacob was able to do? Notice that he didn’t defeat the angel. He was just able to hold his own in the struggle. And what he got out of the struggle with the angel was the blessing.

I think that is one of the blessings of community: how we define and redefine ourselves—and each other—and how we bless each other through the process of struggling with each other. Our job is not to let each other go until we are blessed by the struggle.

This is the tradition of the Talmud, where truth emerges from argument. But for truth to emerge from argument, you need a certain kavanah—a certain intention. Not an intention to be victorious over your adversary, but to build community with the other person.

Let me give you a beautiful example I witnessed recently. Not here, but in another woderful community I have the privilege to belong to: the National Havurah Summer Institute I go to every year.

This year, I attended a series of workshops developed by the organization Resetting the Table to help us communicate with each other over the fraught issue of Israel and the war in Gaza. At one point, I found myself in a small group with two other people. One of the other people felt, as many Jews do, a strong sense of connection to Israel. The other was a young man who considered himself an “anti-Zionist.” To his mind, Israel is a colonial state, without inherent legitimacy, to which he felt no particular connection of allegiance.

But our intention in this exercise—the kavanah given to us by the facilitator—was not to argue our own point of view, but to listen for each other’s truth. After the Zionist participant told us of how at home she felt the first time she visited Israel, the anti-Zionist young man reflected back: “I hear you saying home is where your truth is.”

“Home is where your truth is.”

What a beautiful insight to emerge from an encounter between two people with fundamental disagreements!

My aspiration for this community—for this family of friends—my kavanah, is that we all feel at home here in this way. That, among the many other things that make this place a home for each of us, this community becomes a place where we feel comfortable speaking our truth to each other. A place where we can be fully ourselves. A place where we can be different from each other, and at the same time, connected in community.

Isn’t that a radical notion these days?

I believe it’s something desperately lacking—not only in our country, but in our global culture today.

And I believe it’s possible for us to accomplish this here, in this community. It might be hard at times, but wouldn’t it be a breath of fresh air? I believe we can do it. Be a part of Tikkun Olam, of repairing our little corner of the world right here in Taunton.

We don’t have to start all at once. I’m not asking for an “airing of grievances.” We’ll need to learn how to do it—how to wrestle with one another and support one another and be in community with one another.

On page 78 of our machzor is a beautiful reminder of what community can mean. I’d like to invite our teachers up to celebrate this community with the introduction to kiddush:

Lift this cup for the year that is gone.

For mountaintop moments and the taste of joy; celebrations shared, milestones met, all we’ve mastered and achieved since last we met.

For wedding rings, tears, and kisses under the chuppah; new babies, first words, and first steps;

for the children who bless our homes and bring life to our community; for b’nei mitzvah and confirmands: young teachers of this holy congregation; ours to cherish and guide with love.

For beloved wives and husbands, sisters and brothers; for loyal friends who grow more precious with each passing year; for this community, which nourishes us all.

For all we’ve learned, for all we’ve struggled through, for challenges surmounted and disappointments met with courage.

For last moments shared with those we loved and lost; for parents and grandparents whose memories are with us forever.

We lift this cup for the year that is gone, for the year that begins.

May we meet it in strength, in unity, in hope.

We lift life’s cup and celebrate survival; so may we sanctify each day that is ours.

— Mishkan Hanefesh, vol. 1 p. 78